Racism has been an issue in the U.S. for generations, and it often finds its way into schools.

Just this month, the n-word was spray painted on Allen High School’s Black quarterback’s house. His parents immediately pulled their kids from the school district.

Last week, Lubbock-Cooper ISD passed a resolution denouncing racism, after parents of color sued the district for remaining passive in handling the continuous bullying and harassment of their children.

Incidents like these have occurred across the country and even at our own school.

With minorities making up less than one third of our student body, students of color have reported feeling out of place, uncomfortable and scared to stand up for themselves when faced with racist comments and behaviors.

Racist Jokes

According to UNT Race and Gender Studies Professor Tracy Everbach, students may make racist jokes because they heard them at home.

“If it’s not acceptable in their home, they just might be trying to be provocative, possibly cruel,” Everbach said. “Which sometimes teenagers can be, as a way of gaining social hierarchy.”

Senior June Kim, who is Korean, has heard her classmates make jokes about her race since kindergarten.

“It’s not ever really about just the one specific joke or comment being made,” Kim said. “It’s about the overall buildup of these tiny jokes and microaggressions being built up over several years.”

To fit in with their friends, students of color can even feel pressure to make jokes at their own expense. Senior Rahul Ramesh, who is Indian, used to do this to try to connect with his White friends.

“I stay away from that now,” Ramesh said. “And if anyone I know behaves like that, then they weren’t really my friend in the first place. And the people around me don’t make jokes like that. But when I was younger and more immature, I definitely did.”

Sophomore Vi Ngo, who is Asian, says when minority students actually confront the people who are making the racist comments, they’re usually made to feel like they’re overreacting.

“It’s so ingrained and people feel so normal about saying it,” Ngo said. “And then we are made to feel stupid whenever we get offended by saying, ‘Oh, it’s just a joke.’”

After growing up in Flower Mound for years, students of color have reported having to get used to the undercurrent of racism.

“Me personally, I have become very numb and it doesn’t really get to me anymore, but only because it’s been said to me ever since I was in kindergarten,” Kim said. “And so that should never be a feeling and an experience that people have to endure. Especially at such a young age.”

Everbach encourages students who are being picked on to stand up for themselves. Even if it isn’t received well, she believes it is healthy to speak up for yourself.

“If they don’t believe you, fine…You’ve made progress,” Everbach said. “You’ve gotten to talk about it. And I think that’s what’s important.”

Microaggressions

Microaggressions are a more subtle form of racism. Everbach defines them as words that are hurtful because of someone’s race, gender or sexuality.

“It can be intentional or it can just be out of a result of ignorance,” Everbach said. “But it’s something that hurts another person.”

Ramesh has faced microaggressions from his peers since elementary school.

“People would make fun of my religion all the time, make fun of Indian accents,” Ramesh said. “And I was typically made to feel like an outsider, just because of my skin color, or my culture.”

As he got to high school, the treatment dimmed to stereotyping.

“People won’t make assumptions about you, or your interests or your personality, or your religion or your accent or anything if you’re just a White guy, but people will assume those things about me immediately,” Ramesh said. “They’ll assume I’m a nerd, because I’m an Indian guy with glasses.”

In the classroom, microaggressions can be as subtle as a teacher picking one student out of the entire class to answer all the race-based questions, or as obvious as comments about the student’s race.

Everbach says that because it is hard to admit to having said or done anything racist, it can be difficult to handle being confronted about having used microaggressions.

““Nobody wants to admit that,” Everbach said. “So I think that they get defensive because it’s self preservation. You know, ‘I can’t do that. I’m not a racist.’”

However, she says it is important to consider how the recipient of the microaggressions feels.

“I’ve had microaggressions aimed at me for being a woman,” Everbach said. “You feel pretty horrible and you also lose respect for the person.”

Assimilation

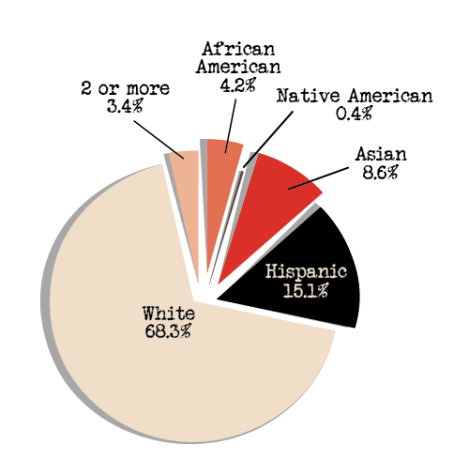

According to the Texas Tribune, the school has a 31.7% minority enrollment rate. While this amount has increased about 7% in the past five years, this still means that less than one third of the population are minorities.

Senior Rahul Ramesh says that in a mostly White community, students of color can find it more difficult to fit in.

“It can be hard as a person of color to relate to your peers, and you can feel more excluded,” Ramesh said.

Junior Harsh Singh, who is Indian, grew up watching Indian movies and listening to Indian music. When he started attending majority-White schools, he felt like he couldn’t interact with his White friends well enough.

“I grew up not understanding a lot of American culture and not understanding a lot of the pop culture references that people would refer to as I was growing up,” Singh said. “And I sort of just had to learn really quickly what those references were.”

While Singh sees and appreciates opportunities like this for students of color to showcase their culture, he says that everyday life feels like it lacks diversity.

“For the most part, it is very Eurocentric and does feel like you just have to immediately understand all of these references and assimilate into American culture,” Singh said.

The Student Advisory Group was created six years ago to brainstorm ways to make all students feel included. This racially diverse group meets with the principal daily to work on ways to unite the different student groups.

To represent the different cultures on campus, they organize a yearly fair called Celebrate Marcus. Students who participate in the fair show presentations about their culture and hand out food.

School-implemented representation

Racial representation on the school level can look like race and culture-based clubs, and events celebrating different people groups. Senior June Kim said that to feel like they belong, students of color should carve out communities for themselves on campus.

While she believes that the school can take steps to make students of color feel celebrated, these efforts should be genuine — not performative.

“To show genuine care and genuine inclusion for all these different cultures, I think that would be something that would be really beneficial to our district and our school and our community,” Kim said.

Matthew Morris is the district’s Director of Diversity and Student Engagement. Morris helps make sure that LISD schools represent students of different backgrounds.

This year, he is focusing on improving the district’s annual Martin Luther King Celebration in January, which the school has hosted for the past three years, and the school’s yearly HBCU fair in February, which is Black History Month.

At the beginning of the school year, Morris chose two or three students from each high school to form a student advisory group that works with him to plan the MLK celebration and the HBCU fair.

“You may not be able to see it right now, but you can’t give up on the work that’s being done behind the scenes,” Morris said.

The school also has clubs that support different races, such as the Black History Club. During race history months, students also give historical fun facts over the announcements — an endeavor that is organized by the clubs.

Regardless of their race, Everbach believes that joining a race based club can be a positive experience for any student. For example, attending Black History Club to learn about African culture can help students be allies to their classmates.

Ramesh says that students have the power to make their classmates feel accepted at school.

“I feel like, as students, it’s up to us to make other students feel like they don’t have to change anything about their culture, in order to fit into a friend group,” Ramesh said.

***

Everbach encourages students of color to open up to people they trust about any discrimination they face. She advises against staying quiet.

“Don’t suffer in silence, because things will only get worse,” Everbach said.