Sophomore Charley David describes living with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, as starting each day with a blank sheet of notebook paper. The tasks she needs to complete are like her math notes.

Similar to how she plans how much space for each section on one page, David plans out her day, giving herself enough time to complete each task.

But as the day goes on, she writes too big. What she thought needs three lines takes up six. The equations grow boring and David finds herself wanting to draw instead, taking up valuable space.

The end of the day comes faster than David expects. She runs out of space — or time — before she can finish everything. This repeats day after day.

“You go, ‘Oh, well, this little section shouldn’t take up much space,’ and then you start on it, and then it ends up taking half the page,” David said. “And you’re like, ‘Well, half my day is gone. What am I supposed to do now?’”

David, who was diagnosed with ADHD in third grade, is taking all of her classes virtually this year, so she doesn’t have a teacher or class periods to structure her day. Suddenly, the pages that represent her days didn’t have lines anymore; she is expected to manage time completely on her own, which she has struggled with since elementary school.

“Sometimes, literally in kindergarten, my teacher gave me a timer on my desk so I knew how much time I had for an assignment,” David said.

This means that like with her leftover math notes, David struggles to finish everything in one day. Even if she wakes up early in the morning and doesn’t stop working until that evening, it never feels like she has enough time.

“It makes me wonder a lot, ‘Was my hard work this morning for not?’” David said. “Because I’ve still been working all day, I could have just paced it differently. It confuses me and stresses me out.”

According to guidance counselor Michelle Schwolert, David isn’t alone. ADHD is the most common neurodevelopmental disorder in kids. People with the disorder often thrive in a structured environment where they can receive guidance and hands-on learning, which is difficult to provide virtually.

“You’re just kind of left on your own and self starting initiative, those are not generally strengths of kids with ADHD,” Schwolert said.

For over a decade, David has been stuck in this battle with her own mind. She knows that she should focus, but sometimes it feels like no matter how hard she tries, her brain won’t do it, instead getting distracted by every little thing nearby.

It’s not that David doesn’t want to do her work. She grew up knowing that she was often behind her classmates. It’s like they were sprinting, but no matter how hard she pushed, she couldn’t do more than jog.

“I have to speed up to get at the pace of everybody else,” David said.

David stood out compared to her neurotypical peers in other ways as well. She never sat still and had anger issues. She had a bad reputation, even though she tried her best to behave like everyone else.

However, it all made sense after she was diagnosed. It was proof that she wasn’t a bad kid. Her brain is just wired differently.

“This impacts me in every way,” David said. “There’s a reason that I’m a troublemaker or feel like I overtalk.”

The first step David and her family took after her diagnosis was learning to manage it.

“I think what really helped is that my mom started to look at stuff for ADHD because I’m the oldest kid,” David said. “So I noticed the way she gave instructions change, like instead of ‘Go do this,’ like, ‘I need you to look me in the eyes. I need you to do this and then this.’”

David was on strong ADHD medication from fourth to sixth grade. Although a prescription is often seen as an effective treatment, this wasn’t the case for David. It severely suppressed her appetite and made it difficult for her to sleep. She always came to school with bags under her eyes and left without eating her snack.

“It was weird because I couldn’t get sleep,” David said. “Probably part of the reason I was underweight is that I just didn’t finish my lunches, and I was supposed to be growing.”

David has been off of the medication since middle school and now takes fish oil supplements. Although her health improved, this meant that she had to learn how to manage her ADHD without a safety net.

“If you don’t have the medication, you can still be successful,” Schwolert said. “It just might be a little harder, and you’ll have to be more intentional about it.”

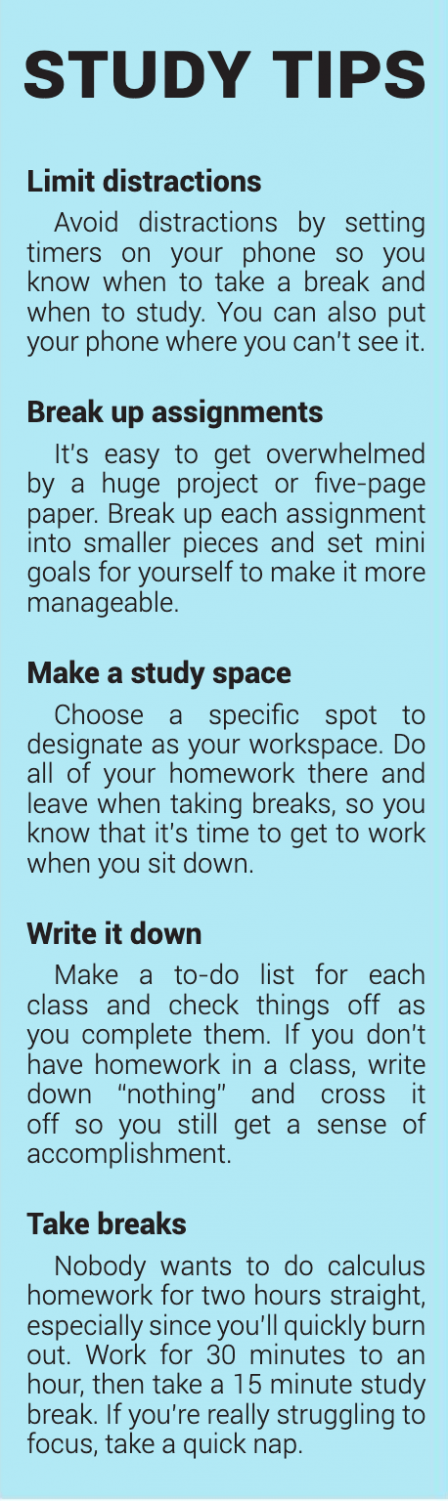

David has used these strategies while learning from home. After a few weeks of trial and error, David began to enjoy the freedom of virtual learning.

“If you do it right, you can be a lot more productive than you are at school,” David said. “You can pace yourself like you want to. You can order your classes depending on how much attention they require.”

David considers herself lucky. She was diagnosed with ADHD early, so she has had years to learn how to win the fight against her own brain.

She said that this is what it comes down to when someone is diagnosed with ADHD — figuring out what works for them and having self control. This can be the difference between passing a class with flying colors or turning every assignment late, especially when learning virtually.

However, David said that it’s a learning process. She hopes students in a similar situation won’t give up, as everyone has the capability to be a great student, even if they think differently or walk a few steps behind their classmates.

“By the end of the day, you don’t have to have it all done, so don’t be upset at yourself when that’s not the case, because you can make up time,” David said. “That time is flexible, but you should still have motivation.”