A second chance

Teacher recovers after near-fatal surgical complications

January 31, 2020

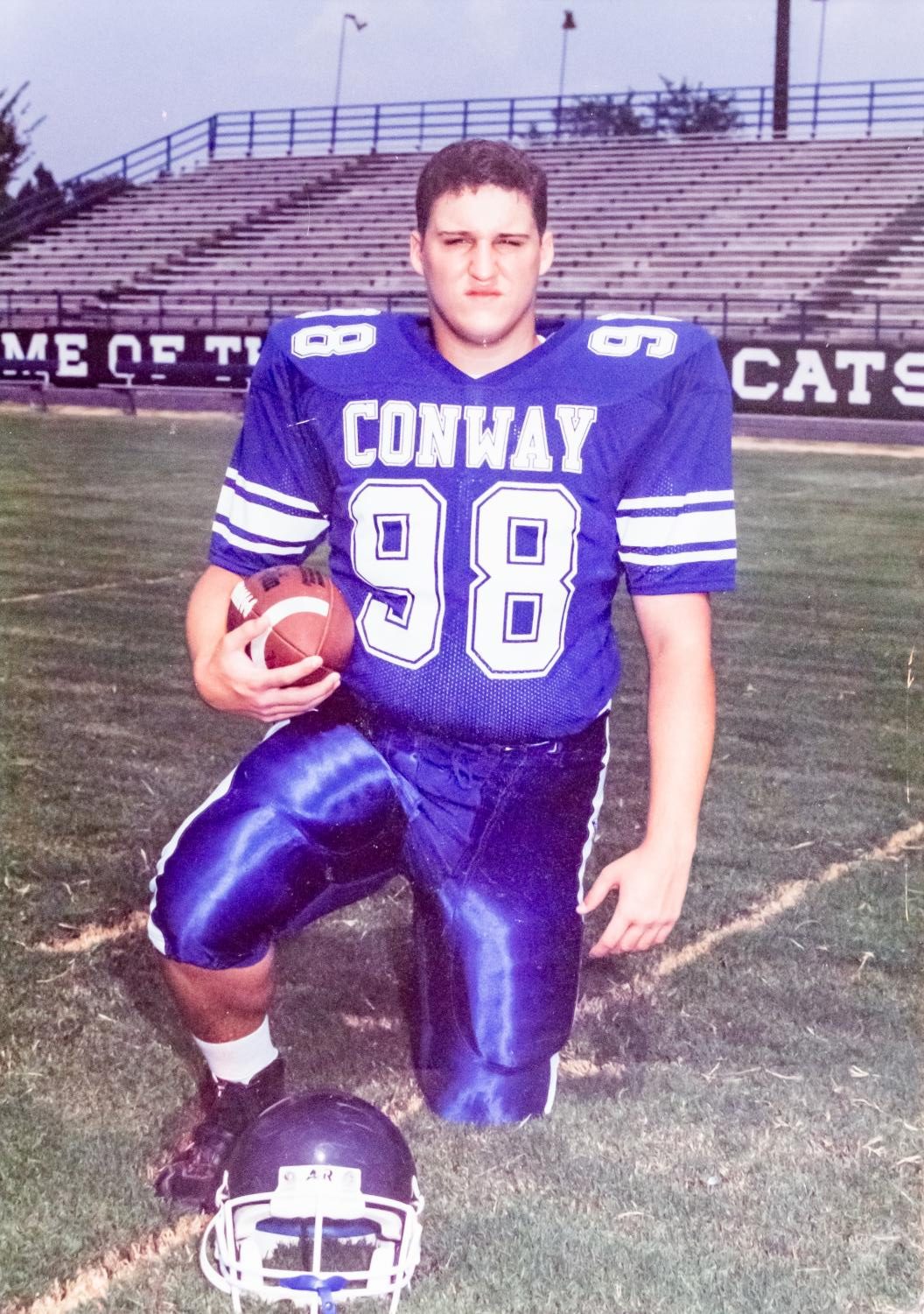

Journalism teacher Corey Hale was always bigger than most of his peers, but playing football helped him manage his weight.

Editor’s note: This story won first place for general features in the 2020 Columbia Scholastic Press Association’s Gold Circle Awards. It was named as a superior feature in the TAJE Best in Texas contest and it won second place for features in the Press Women of Texas high school contest. It also won first place and Tops in Texas for online features in the ILPC contest. It was also included in the portfolio that won first place for writer of the year in the 2020 National Scholastic Press Association individual awards competition.

The man he saw in the mirror wasn’t him. He barely recognized himself in the overweight college freshman who stared back.

He still felt like the high school senior who played football. Back then, he was 6 feet 3 inches tall and weighed more than 300 pounds, but he wasn’t concerned. He towered over his classmates since elementary school and ate whatever he wanted. He’d burn it off in practice anyway.

But that kid was gone. The comfort he found in food, however, remained. He ate Taco Bell and pizza to cope with the anxiety and depression that drove him to skip class and stay in his dorm.

Within a year of starting college, he had put on 50 pounds. Soon, 50 became 70. With each new pound, he isolated himself more. His friends invited him to the movies and Mavericks games, but he rarely went. He couldn’t fit in the seats.

Surgery

Something had to change. He wanted his life back, and he almost lost everything to get it.

For 15 years, journalism teacher Corey Hale was stuck in a cycle of bad eating habits, increasing medical problems and blinding self-reliance.

Eventually, he was too heavy to use a regular scale. When he used a special one and saw 409 pounds, reality hit him. He couldn’t lie to himself anymore. The number he saw now started with a four.

He could handle a three. He convinced himself it was OK because of his past as an athlete.

But at 409 pounds, he felt like he was going insane.

“The old definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result, and that’s kind of where I was,” Corey said.

Corey tried everything to lose weight, but nothing worked. As his weight continued to rise, he suffered from anxiety, depression, high blood pressure and obstructive sleep apnea. Finally, he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

“When they tell you you have type 2 diabetes, you just think, ‘I’m going to have this for the rest of my life,’” Corey said.

After that diagnosis, his doctor recommended weight loss surgery. Corey was unsure. It had a 99 percent survival rate, but he wasn’t worried about his safety. He didn’t want the “easy way” out. The highest number Corey ever saw on a scale was 471 pounds, but he was still convinced that he could lose the weight on his own.

His doctor disagreed, insisting this surgery was likely the only chance Corey had at being healthy again.

“It was that window of opportunity,” Corey said.

Corey decided to make a change and scheduled his surgery for Aug. 13, 2012. It seemed to go well, and he was out of the hospital within a few days. Though he was in a lot of pain, it was his first time having surgery, so he assumed the discomfort was normal.

On Aug. 24, Corey sat in his empty classroom at Lewisville High School, preparing for the school year, but the pain made it impossible. Coworkers looked at his colorless face and grew concerned. The Corey they knew turned the school newspaper into an award-winning powerhouse and recently won Teacher of the Year. They continuously asked if he was OK. Corey had the same answer every time. He just had surgery. He was just trying to get by.

That afternoon, he had a follow up appointment, but the doctor said his pain was normal and sent him home. A few minutes later, it became unbearable.

“I pulled over on the way home because I could barely drive,” Corey said.

As soon as he got home, Corey took pain medication, but threw it up. Suddenly, a radiating pain shot throughout his whole body.

“It was one of the worst pains I’ve ever felt in my entire life,” Corey said. “I was like, ‘Nothing about this is normal.’”

One of his internal sutures from the surgery had opened, causing an infection. He had developed sepsis, or blood poisoning. His organs were about to fail. Corey was at risk of being part of the one percent.

“I’m literally dying on the inside, not even metaphorically,” Corey said.

His roommate called an ambulance, but Corey was still more than 400 pounds. When they arrived, it was difficult to move him, costing them valuable time.

The sirens wailed as the ambulance sped to Denton Regional, where his surgeon was prepping for emergency surgery.

He saw one of the assistant principals from Lewisville High School as he was wheeled into the operating room.

The faces of his surgeon and anesthesiologist are the last thing he remembers.

He wouldn’t be conscious again for weeks.

Comatose

Casey Hale gripped the steering wheel as she sped down the highway. Music streamed out of the car radio, but it did nothing to silence the thoughts racing in her mind.

Is Corey going to be OK? He has to be.

Casey drove for six hours straight from Arkansas, too worried about her older brother to even stop. Though she already knew that he was out of surgery and in a medically induced coma, 25-year-old Casey couldn’t help but fear the unknown.

I need to see Corey. Will he wake up? How was this happening? Please God, let him be OK.

Her phone rang, bringing her back to reality. Another family friend was asking her for an update. She answered countless phone calls from worried friends and family during the drive.

“I felt like it was probably one of the longest drives that I’ve ever made,” Casey said.

When Casey arrived, Corey was already in a coma in the ICU. The doctors needed to intubate him and figure out how to treat the infection.

“I remember being kind of in a state of shock,” Casey said. “I had just never seen my brother in that kind of condition. To me, he’s always been my big brother and he was so big and tough and strong, and he just looked so helpless.”

Casey was at her brother’s bedside when-ever she could. She told him jokes to try to get a reaction. She laid her phone on his pillow and played his favorite songs to drown out the beeping machines and whispering doctors, just in case Corey could hear them.

Corey holds his niece Ava Grace. He tried to lose weight himself with different diet and exercise programs for 15 years before deciding to get surgery.

“I knew that my parents were really struggling and were really scared, so I tried to just stay upbeat,” Casey said. “If I talked to him, I tried to be real positive and just make the room a little bit lighter.”

Casey also sent daily updates to 85 people, who then passed them along to their friends and prayer groups. Though it was difficult, she tried to be uplifting.

“I wanted to have a positive every day so I tried to kind of keep that, but it was difficult to do because I was really scared,” Casey said.

When things got to be too much, Casey stepped out into the lobby and called her friends back home. She’d let go of her fear and grief and allow herself to cry.

On Sept. 2, Corey took a turn for the worst. His temperature rose to above 103 F and his breathing was labored. The doctors used countless ice packs and medicines to try and control his temperature, but they began to lose hope. They told Corey’s family to say their goodbyes.

“That was devastating,” Casey said. “My dad was really strong in that moment and just said, ‘This is not happening. We’re not going to lose him,’ but everybody was really, really scared.”

Casey refused to give up. She typed out an update.

“We are needing immediate prayer… we know that our Father is the ultimate physician,” Casey wrote. “He can do all things, and He doesn’t depend on modern medicine to do so. Please join me in praying for miraculous healing.”

Those 85 people sent out the urgent prayer request and hundreds of people from all over the country prayed, including his students and coworkers at Lewisville. Assistant principal Kyle Smith was a special education teacher at Lewisville at the time, and when he heard that Corey was having surgery, he expected him to be back to normal soon. Now, nobody knew if he would ever be able to teach another class.

“In the department down there, it kind of left a big hole,” Smith said. “You can’t believe that he’s not there. You go by his room or you go into his room and you expect to see him.”

On Sept. 3, his doctor decided on another surgery to find the infection. The waiting room was crowded as 25 people paced across the floor and prayed.

“I think it was a matter of a couple of hours, but it definitely felt like a lifetime,” Casey said. “Towards the end as we were waiting on the results from the surgery, it was really incredible to see the outreach that everybody poured out.”

At 8 p.m., their prayers were answered. A nurse called them from the operating room. They found the source of infection.

“I remember us just screaming and celebrating and high fiving,” Casey said. “The operating doors opened and the nursing staff came out that were with him, and they were giving each other high fives and jumping around. I think everybody knew how intense it was and how on the verge of losing him we all were.”

Waking up

On Sept. 8, Corey finally opened his eyes for the first time in weeks, although he wasn’t aware of it. His mom just wanted to see her son’s eyes again. He had a tracheostomy a few days later. His earliest memories are a week later on Sept. 15.

“Even though he couldn’t talk, we were able to communicate pretty clearly and I was laughing and joking with him,” Casey said. “It was just so good to see his eyes open and him look you in the eyes again.”

When Corey awoke, he recognized his mom but didn’t know why she was there or where he was. His family was overjoyed to finally see him awake, but he was miserable. They were the ones who waited for weeks, unsure if he’d make it through each night. Since August, Casey and their dad had been driving in from Arkansas every weekend. Their mom uprooted her life to move to Texas and stay with him, and she wouldn’t leave his side until he was able to go home.

Corey, however, didn’t know how close he was to death. He just woke up to weeks of his life missing and a body that no longer worked — he lost so much muscle mass and weight during the coma that he could barely lift his head off the pillow.

With time, Corey’s mom explained everything that had happened. Even when he was able to start processing what was being said, Corey was unable to talk due to the tracheostomy. His mind raced with countless questions about what was yet to come.

Will I ever walk again? Will I ever talk again? Will I sing again? Will I get to stand up and teach a class again? Who’s with my students? What’s the newspaper staff doing?

But he couldn’t ask her because of the hole in his throat.

“I’m just trapped inside my own brain,” Corey said. “I can’t ask those questions, and nobody knows those are the questions that are on my mind. I just remember her telling me all this, and me just rolling and turning my head the other way. I just wanted to go back to sleep.”

The ventilator was unhooked and completely removed from his room on Sept. 18. Though most people are only on one for a few days, he’d had to stay on it for almost a month.

Even after the initial effects of the coma wore off, Corey was still stuck in a battle against his own mind. He was in the ICU for almost a month with beeping machines, white walls and lights that never turned off. An automatic blood pressure cuff tightened and released around his arm around the clock.

People rarely stay that long in intensive care. The days blurred. Minutes felt like hours. He was trapped, but he had no way to escape. Corey used to turn to food to cope, but he couldn’t keep up the same unhealthy habits after surgery.

“It was hard and it was slow and I wasn’t the best patient,” Corey said. “I was really angry… It was tough because I didn’t really have any way to express it.”

Anybody who knows him knows he loves to talk and ask questions. Teaching journalism was his life. But nobody knew if he would ever be that person again. The weeks of lying unconscious in a hospital bed left his mind hazy. He was easily confused and overwhelmed.

If Corey closed his eyes for what felt like a second, he had vivid hallucinations. When he opened them, everyone was still there.

“I was trying to cope with some of the weird things that happened in the ICU,” Corey said. “It was super vivid and then once they moved me out of the ICU, I didn’t even remember a single dream that I had.”

Corey faced near fatal complications after his surgery in 2012, but he doesn’t regret it. Before, he used to wear size 5XL clothes, but the procedure allowed him to lose enough weight to wear XL.

One of the few things that brought Corey comfort was watching the Weather Channel. His family tried to get him to watch the presidential debates or football, things he used to love. Corey refused. It was all too much, but he could deal with the weather.

“It just let me have something steady and normal,” Corey said. “I kept hoping that they’d take me outside at some point.”

Corey felt helpless. The first day he tried to sit on the edge of his bed, he couldn’t hold himself up.

“It was just the cross between humbling and humiliating,” Corey said. “It definitely stripped me of any kind of pride that I had.”

Corey spent a month relearning to sit in a chair. To stand. To walk with a walker.

He hit a milestone when he took 25 steps without a walker. That afternoon, 477.

“A wise person told me, ‘They will fix your body, but they won’t fix the things inside you that will lead you to do this to yourself. You’re going to have to find different ways to deal with those emotions,’” Corey said. “That was one of the truest things that anybody’s ever said to me.”

As he recovered, the Lewisville community rallied behind him and hosted a spaghetti dinner fundraiser to help with Corey’s medical bills. Even people who normally didn’t get involved with similar events showed up to donate. To Smith, it was like watching a family come together to help one of their own.

“It just warms your heart,” Smith said. “You hate to see somebody go through struggles, but then it also reinforces your belief in mankind. When somebody is in a bad spot, everybody on the team pulls together and helps anywhere they can.”

In late October, Corey was finally able to go home. Only months ago, Corey had been sitting on the side of the road, his pain making the trip seem impossible. Now, he could drive himself home.

Road to joy

Corey jumps over a small stream on a beach near Seattle after losing over 200 pounds from the surgery.

Corey returned to his classroom in January of 2013. Although getting back into the routine he had before the surgery was difficult, it helped him recover more than anything. Lewisville welcomed him back with open arms. His life was finally getting back to normal.

“Everybody was excited to see him and greeting him and concerned about his health still, but it was a joyous day for sure,” Smith said.

Corey’s aunt promised him that if he pulled through and got out of the hospital, she’d take him on a trip to anywhere he wanted. He chose San Francisco. Corey fit in a normal plane seat and stood in the chilly waters of the Pacific Ocean.

In the next few months, he experienced everything he isolated himself from years before, going to the movies and Mavericks games and another trip the following year. This time it was to Seattle, where he hiked 12 miles up a mountain.

Corey loved the Northwest, but it was a few weeks later when he was driving on a quiet East Texas road that the reality of everything that he went through hit him. The early morning light peeked through tree branches above his car. Corey was on his way to Tyler to meet his newborn niece, Joy.

It had been less than a year since Corey’s surgery and he was still trying to process everything. When he sat down in his car early that morning to start the trip, Corey didn’t feel like he was lucky to have survived, but that changed as he drove.

Two years after surviving complications of weight loss surgery, Corey met his wife. They have a 2-year-old son. Before the procedure, Corey never really considered that he’d ever have the opportunity to have his own family.

“That was a moment, just driving out there going to see my new baby niece and just thinking that this really is a blessing and a privilege to be alive,” Corey said.

Corey has been asked the same question countless times since his surgery, and it’s the easiest one for him to answer. Would he do it again?

The answer is always yes without hesitation. The surgery nearly cost Corey his life, but his lifestyle was slowly killing him before. His quality of life declined with every diagnosis and every day spent alone. Having his own family in the future never seemed like an option. It was like he was drowning and the surgery was the only thing that could bring him to the surface.

Now, almost eight years since he woke up from the coma, Corey doesn’t have a single doubt that it was worth it. He has lost more than 200 pounds and his medical conditions were reversed. He now has a 2-year-old son with his wife of four years. He is healthy enough to be the dad and husband he wants to be.

“You wake up from something like that not really understanding how much people care about you, especially for me, who struggled at different points in my life with depression and with doubts about my self worth,” Corey said. “Seeing that outpouring of support from so many people… there’s no way that I deserved that much kindness from people, but that’s what they did.”